The almost ideological debate

It was since 2015 when Martin Fowler advocated starting a new project with monolith-first in his blog. Six days later, Stefan Tilkov advocated almost the exact opposite proposition, and yet these two articles were hosted on Fowler’s website. Tilkov’s argument of not starting with a monolithic was predicated on if microservices was the goal of the architecture. And of course, there were also tons of articles and blogs of “How to break down a monolithic into microservices” on the Internet.

Is microservices the new rising star and monolithic-first a paradigm in the past? Not really. Or, are we able to choose one school of thoughts and be ok with it? No either. The monolithic-first or not debate, almost sounds like choosing an ideology to follow, is not really the answer. Religiously or blindly following a pattern without understanding why is an anti-pattern itself. I believe we weren’t asking the right question.

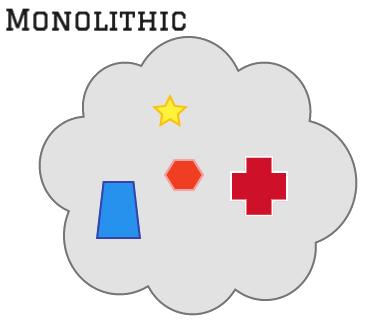

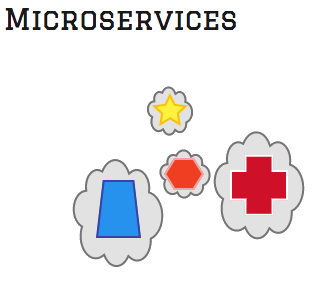

Monolithic and microservices are good for some systems and bad for others. It has multiple layers of concerns. Sometimes a mixture of both is the best pragmatic approach. It however leaves some more complicated questions. When to use which?

Going concern

Similar to the Going concern in accounting terms, we normally would assume that a software system will be able to continue operating for a period of time that is sufficient to carry out its functions. Otherwise, it’s metaphorically delivering a dead baby - the system is dead at the time of birth. However irony it may sound, there are a limited number of cases in which you may really need such a temporary function. Of course if you do need to develop a temporary tool, do it quick in the simplest way and the most productive way, and monolithic-first is recommended.

The major drives of going microservices are the going concern and expansion. If you anticipate the system in your project is going to operate for years to come, and with expansion planned in the future, then your system needs to be designed to evolve over time. To be able to evolve efficiently, you need to be able to replace and enhance a part of the system without breaking the it down. Each part of the system need to address an independent unit of the architectural concern separately. So the term comes out - “Separation of concern”.

Separation of concerns

The term “Separation of concerns”, according to Wikipedia, was probably coined by Edsger W. Dijkatra. As I am not able to explain better than he did, so I just quote it to you:

“Let me try to explain to you, what to my taste is characteristic for all intelligent thinking. It is, that one is willing to study in depth an aspect of one’s subject matter in isolation for the sake of its own consistency, all the time knowing that one is occupying oneself only with one of the aspects. We know that a program must be correct and we can study it from that viewpoint only; we also know that it should be efficient and we can study its efficiency on another day, so to speak. In another mood we may ask ourselves whether, and if so: why, the program is desirable. But nothing is gained —on the contrary!— by tackling these various aspects simultaneously. It is what I sometimes have called “the separation of concerns”, which, even if not perfectly possible, is yet the only available technique for effective ordering of one’s thoughts, that I know of. This is what I mean by “focusing one’s attention upon some aspect”: it does not mean ignoring the other aspects, it is just doing justice to the fact that from this aspect’s point of view, the other is irrelevant. It is being one- and multiple-track minded simultaneously.” - Edsger W. Dijkatra, 1974, “On the role of scientific thought”

I have a rather naïve way to interpret it. Every unit of a system should serve one and only one purpose, be it functional, be it performance, be it usability, but not a mix of any. As a result, you have one and only one reason to change a unit. This is essentially the Single Responsibility Principle. Once you have it, your worry of refactoring should be largely reduced, and of course I assume you have a well-covered test suite to verify your evolving system.

This would explain my strong inclination to functional programming because each file has only one publicly accessible function that does one conceptual unit of work only. I am not able to do it with object-oriented programming.

Evolutionary systems

If your system codebase is organised to separate concerns like we have just mentioned, then your system should be ready to evolve. Evolving does not necessarily mean going microservices though. A big singular monolithic is like a unicellular organism, it can only break into smaller cells and hence going towards microservices. However, for complex organisms, when a part of the system is severally under-used over generations, it ceases to exist or combines with other parts of the system, and hence going towards monolithic.

So monolithic or microservices should be the result of natural architectural evolution.

That mostly leads to the conclusion to the question that was explored in the beginning. We know that human evolved from unicellular organisms billions of years ago, so similar monolithic must be the right thing to do for a new project?? Almost right, but not exactly.

Starting a brand new system

If you start a new system with no existing system to refer to, or a new system with lots of unknowns to both developers and business, then monolithic would make more sense. It is not because the monolithic is the final architecture that we need in the future; it is because a big monolithic gives the best opportunity for the system to evolve organically. In this sense, both business and developers can avoid prematurely making decisions for the problems they do not know enough, and hence avoid wasting effort in the meantime. It is better to code for the knowns, and delay coding for the unknowns until you understand the problem. This is in line with the YAGNI principle. This is also in line with how to human works in general, as we are constantly evolving, learning, and improving the way we work. We are not good at doing it right the first time.

Rewriting an existing system from scratch

If you are going to re-write an existing system, then things become more complicated. You have knowledge, experiences, may be traumas about the system. You have some lessons learnt already. You may even have tried to break a monolithic into microservices but failed.

A safe approach to re-write a system is keeping all components and their interactions the same. All high-level flows the same. Just modernising the underlying technology or the codebase. But the value for the re-write is usually not high enough, because the safest of all is simply not changing anything! Almost all system re-writing projects aim to improve what was not possible with the current architecture.

If your existing system may be a big single monolithic, or a polylithic consisting of a few big applications, or may even be a microservices architecture gone too far. This is the golden opportunity to put things right. Dividing the system into applications right is really the key here. This can also happen after a monolithic system ran for a few years, and you have learned enough lessons that you feel you are ready to break it down.

Moving things around

There are a number of criteria that could guide you into breaking down a monolithic. They are not the always the golden rules and a pragmatic approach should always be taken. It is always better to break a monolithic in a small scale but appropriately, than to do it wrong in a large scale and suffer the consequences. Sometimes breaking it down in baby steps unveils the true nature of the problem incrementally. You do not get to see the whole picture unless you make a number of careful and small moves. Evolution is never a big bang process.

Performance and scalability

Operations can be differentiated by their non-functional requirements. The system generally does not perform well when mixing operation of different performance characteristics, because optimising the performance of one operation almost certainly will sacrifice the others.

For example, given an application provides the following two operations:

| Operation | Throughput | Size | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recording | 20 per sec | 2KB | 10 ms |

| Search | 5 per day | 200KB | 2 secs |

In this example, the recording operation requires higher throughput and lower latency, but the data for each operation are smaller. On the contrary, the search operation only run five times a day and can take 2 seconds for large data size. If we optimise the recording operation by appending the records in a journal, it would make the search inefficient for the full journal scan; If we optimise the search operation by indexing the data while recording, then each recording will involve computation which increases the latency.

For the sake of simplicity here, we could divide this application into two :

- Journaller : write the transactions in a journal (e.g. a file) as quickly as it can

- Searcher : tail from the journal and organise the data into indexed structure for query

To extend it further, if there are two types of search - by time range and by name, we could potentially further divide the Searcher application into Searcher-by-time-range and Searcher-by-name, whereas they index the data a bit differently.

Domain and responsibility

Another way is the division of bounded-context. Usually a well-sized microservice should have only one aggregate, which is a collective unit of domain entities. And there is always an entity being the central focus with a bunch of related entities around it. You should be familiar with application names like UserService, AccountService, etc., as “User” and “Account” are the Aggregates. On the other hand, if two applications are identified to share the same Aggregate as the central focus, they should probably be merged into one.

The bounded-context can be defined as a part of the Domain-driven development process, which will involve Event Storming and development of Ubiquitous Language. Bounded-context is also the foundation of getting Event Sourcing and CQRS right.

Due to the depth of this topic, I will not attempt to explain into how to divide monolithic by Domain-driven development methodology. However, there are several indicators that you are in the right path:

- There is only one Aggregate in your application

- Operations in your application are cohesive

- Operations in your application have very few or no dependency on another application

- Operations in your application have no inter- or circular-dependency on another application

- You share no entities, commands, querys, nor events with other applications

Resilience and recovery

Sometimes a monolithic is divided into applications that have similar operations but of different flavours. The goal is slightly different from the previous two approaches. There are a couple of examples:

- You have multiple types of external connections and you want independent failure

- You have clients from desktop and mobile devices that use similar but different sets of APIs of your application (Ring any bell on Interface Segregation Principle?)

- You have multiple downstream applications that requires the same data but in different formats

The basic principle is about moving from total system failure to minimalised service degradation when things go wrong. Ideally the failed part shall not bring down the healthy part. Doing it right should make the system as a whole more resilient. It also buys the system support some time to recovery the system as part of it is still operational.

This is different from redundancy and replication because the divided applications are similar but not the same. The difference could be in the protocol, the data format, or the API.

Usage and cost

Merging microservices into monolithic is relatively unusual, but if you are burning your budget in maintaining a bunch of applications that has low usage, and probably you are also under-utiltising the expensive technology for this, say database or message broker, then it is perfectly valid to make it monolithic.

However, be mindful about what we are trying to achieve. If cost-saving is the goal, then we should quantify it, for example:

- Maintenance cost of multiple applications. The time spent on git operations, pull-requests, code review, release, deployment for multiple applications can be reduced by having just one application.

- Maintenance cost of multiple servers. If the server is virtualised or containerised, then the impact is small. If the server is physical, then you would not want to keep that many servers with each core running low usage.

- Technology used for service communication. This is probably the biggest part of the saving. By merging microservices into monolithic, the transport (e.g. REST, JMS) is reduced to nothing more than a function call. The next thing to save is any technology used to support the transport. It could be an HTTP load balancer, a JMS message broker, or a network link.

It is worth to note that merging microservices also brings cost and risks. The cost is usually small and one-off. As the service is not used in anger anyway, the risk should be small, at least smaller than splitting monolithic into microservices.

A quick comparison

Having gone through all these, it is probably fair to say that we still need a quick comparison between monolithic and microservices. The suitability between the two depends on the stage of your application evolution. If you had to fight all the way to get the interaction among applications right for a function, the system may be over-divided into microservices. Then it’s probably time to review and evolve again.

Pros :

- Smaller development overhead (git operations, release and deployment)

- Very easy to test the system as a whole

- Able to carry on development when technical decision has not been made

Cons :

- Risks of spaghetti structures

- Disruptive single unit deployment

- Potential single point of failure

- Potential long build time

- Difficult to scale up performance

Pros :

- Independent deployment

- Can be continuously delivered

- Independent failure

- Shorter build time

- Easier to scale up performance

Cons :

- Bigger Development overhead (git operations, release and deployment)

- Complex to test the system as a whole

- Risk of inter-dependent services and circular dependency

- Change of technical decisions could result in a lot of re-work